Developing Information Literacy Skills in First Year Students

First year students experience lots of new things when they come to college: new friends, roommates, campus food, new organizations, new professors, and new challenges in the classroom. For some, college may be the first time they are asked to write a substantive research paper using scholarly, academic sources.

As it turns out, figuring out what sources to use in a research paper doesn’t come naturally to most people. Students may wonder: how do I figure out what my topic should be? How do I know if it’s too broad or too narrow? What information is accurate and what’s not? Who’s an authority on this topic? How do these sources talk to one another? How do I make sure to give credit to sources while building my claims?

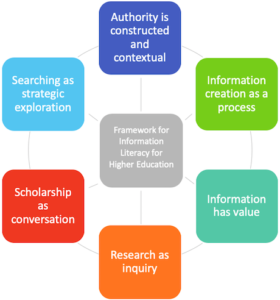

Enter information literacy, an AAC&U essential learning outcome of a contemporary liberal education. The Association of College and Research Libraries’ current information literacy framework organizes information literacy into six major conceptual areas.

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation as a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship as conversation

- Searching as strategic exploration

Wallace Library sports a robust information and technology literacy instruction program. Liaison librarians teach more than 100 class sessions every semester. They meet with almost every First Year Seminar (FYS) two times. In these meetings, students begin building information literacy skills because liaisons helps them tackle two major topics: fundamentals of research and the ethical use of information. As a result, students get hands-on experience exploring the ACRL information literacy framework concepts.

The fundamentals of research session speaks to several of the frames. For example, using library search tools touches on searching as strategic exploration. Understanding authority ties to authority is constructed and contextual. Discussing which formats to use in academic settings addresses information creation as a process. And finally, generating topics and keywords connects to research as inquiry.

The ethical use of information session addresses the other two concepts. Because information has value, researchers should use it ethically. And since scholarship is a conversation, students practice identifying parts of a citation, knowing when to cite, exploring citations as conversation, and avoiding plagiarism.

First year information literacy instruction exposes students to crucial skills. As they move to 200- and 300-level courses, they dive deeper into disciplinary topics. Fortunately, many faculty continue to partner with liaison librarians on course and assignment development, so students get the opportunity to develop more sophisticated approaches to working with information as they advance through college.

Our goal in the library is for Wheaton students to graduate as information literate citizens of the world. This instruction program, particularly the First Year Seminar portion, is one major part of achieving that goal. Faculty members who want to learn how to integrate information literacy concepts or instruction into classes and students who want to improve information literacy skills can consult with a library liaison for expert help.

-Megan Brooks, Dean of Library Services