“Look Again” and See Yourself

Emily Swalec

“Ken Aptekar: Look Again,” February 6-April 14, 2012

Emily Swalec ’14

Detroit-born artist Ken Aptekar is acutely aware of the “baggage of high art” that confronts most people entering art galleries or museums. In an attempt to transcend the division between those who “get” art and individuals who feel alienated by it, Aptekar repaints works by a wide range of artists and then bolts glass sandblasted with text over the paintings. These texts—ranging from succinct musings on the messages of specific works to personal statements by the artist and others—encourage viewers to trust their individual reactions to art. Aptekar believes that everyone is capable of “rich responses to art,” and in his current exhibition at the Beard and Weil Galleries at Wheaton College, he urges viewers to Look Again, to break down the boundary between past and present, and to make personal connections with art.[1]

Museums can potentially make viewers believe that there is a right and wrong answer when looking at a work of art. Wall texts often prioritize historical details, or art historical approaches (such as formalism) to works of art. As David Freedberg writes in The Power of Images: “Much of our sophisticated talk about art is simply an evasion. We take refuge in such talk when, say, we discourse about formal qualities or when we rigorously historicize the work, because we are afraid to come to terms with our responses.”[2] Not only are many viewers fearful of their own responses, but they have also been conditioned to ignore immediate, unsophisticated reactions to art that might not be acceptable in the art world. Ken Aptekar, however, is not afraid to acknowledge his own responses to art and encourages others to do the same.

Aptekar’s work critiques the ways in which art institutions attempt to shape how viewers interact with art within their walls, either as a means of asserting authority or as a way of discouraging highly personal responses to art. He does not believe that paintings have one clear, easily defined meaning that can be taught. As Aptekar stated in a recent gallery interview: “a painting is alive in the relationship with the viewer, so depending on who the viewer is and what they’re thinking at a given moment in a particular point in time in history that meaning changes. It’s not fixed, and it resides in the space between the viewer and the work. It’s not implicit in the work alone.”[3] A viewer’s individual response to a work is always valid for Aptekar, because that response is the work’s meaning in that moment.

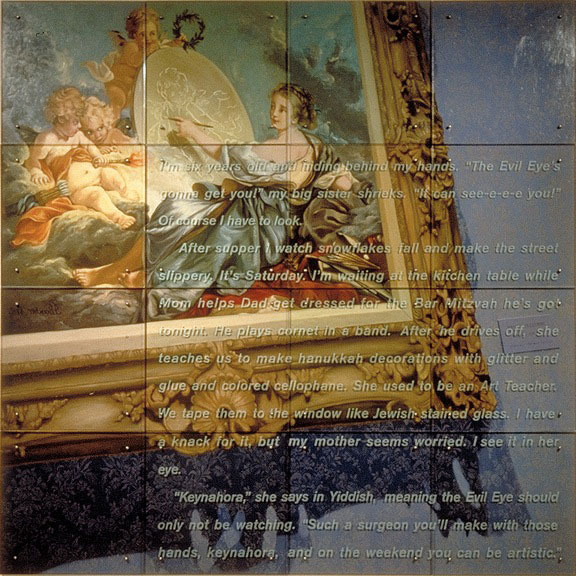

To this end, Aptekar works to “drag the past into the present” by connecting historical paintings to modern life through the inclusion of text.[4] The centerpiece of the exhibition, displayed alone on a bright red wall as one enters the gallery, is a work by Aptekar from 1996 entitled I’m Six Years Old and Hiding Behind My Hands. This enormous ten-foot-square painting is a reproduction of Francois Boucher’s Allegory of Painting (1765). Aptekar crops Boucher’s painting, showing only the bottom left corner of the image where a female allegory of painting appears with several putti. A large gilded frame, which Aptekar added to the original painting, casts a shadow on the blue wall included in the work. This shadow mirrors the dark autobiographical text overlaid on the painting. In it, Aptekar describes a childhood memory of a conversation in which his worried mother discouraged him from becoming a painter despite her background as an art teacher. With this introduction to his exhibition, Aptekar invites viewers to make distant, intimidating works of art personal, just as he has with this text. The woman in the painting is no longer centuries away from the viewer; she potentially becomes Aptekar’s mother, and, by extension, the viewer’s own mother is brought into the work. Past meets present, and Aptekar’s paintings become accessible to the viewer as he encourages “intrusions of real life.”[5]

These intrusions are embodied by Aptekar’s unique method of bolting glass to his paintings. Aptekar makes it clear that viewers are free to impose their thoughts on the work, just as he has directly bolted text to each painting. The two become inseparable. In fact, for Aptekar, the works have no meaning without a viewer; they are simply “dead objects.”[6] Only when viewers engage in “conversations” with the art are the paintings activated. In addition to containing the message attached to each work, the glass reflects the image of the viewer standing before the painting. As viewers come and go, new figures are added to the painting through the reflection, emphasizing Aptekar’s belief in “changeable reception.”[7] The painting exists only in that moment for a specific viewer, and the viewer is an integral part of the work.

For viewers who are intimidated by the thought of letting their thoughts about art flow freely, Aptekar makes it clear that here any response is valid. His text is often humorous, a technique he uses to break down the fear of authority.[8] A Reason to Wake Up (2005) juxtaposes the positive affirmation “A reason to wake up each morning,” in a bold capitals with a reproduction of Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s Chasse au loup (1734). The painting depicts a pack of snarling dogs mauling a wolf cornered at the base of a tree. Aptekar recasts Oudry’s painting in a red-orange palette reminiscent of blood. This shift in color captures what the painting means to Aptekar. By heightening the violence of the image, Aptekar also makes the text seem ironic or even mismatched. It is not a proper, museum-certified response to Oudry’s painting, and yet, Aptekar considers this response as legitimate as any other. The cynical spin appealed to Aptekar’s collector who loaned the work to the exhibition; she hangs the painting over her bed.[9]

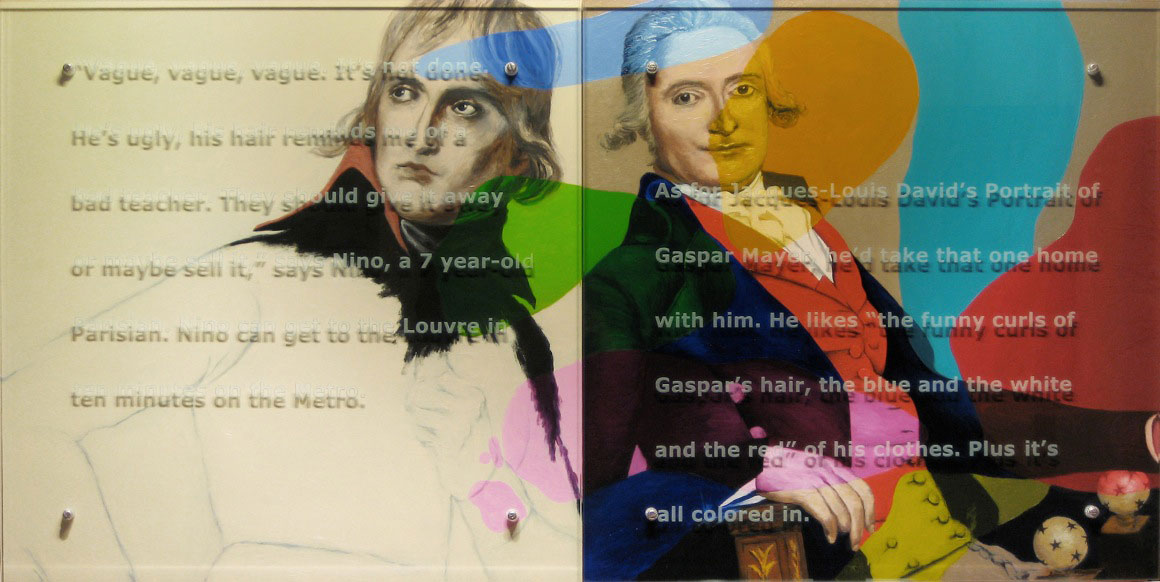

While Aptekar’s autobiographical texts, succinct messages, and humorous musings on paintings may be enough to entice some viewers to project their own thoughts onto the works of art in the exhibition, they may also be misconstrued as another form of authority, a definitive interpretation that Aptekar forces upon the viewer. To affirm the value of the viewer’s opinion in his work, in 1996 Aptekar began to talk with focus groups about pieces of art while working on the Talking to Pictures exhibition for the Corcoran Gallery of Art.[10] Since then, Aptekar has sometimes used quotes and personal stories from individuals other than himself as the text for his paintings, increasing the viewer’s role in his work. Three of the strongest pieces in the Look Again exhibition are Aptekar’s nontraditional takes on portraits, which give viewers direct control over the meanings of the works. Aptekar describes these pieces as “portraits that [do] not show the actual physical person but that [show] how they looked at paintings and that [use] how they looked at paintings to reveal who they are.”[11] The portraits are displayed with a video of the interviews Aptekar conducted with the subjects, allowing viewers to see how Aptekar captured the subjects’ personalities and how one can freely express his or her thoughts about a piece of art.

Portrait of Nino Alcock-Boselli (2010) conveys the innocence and humor of a child’s response to art. During a trip to the Louvre, Aptekar asked Nino, the then seven-year-old child of family friends, which painting he would like to take home and which he thought should be removed from the collection. Nino rejected Jacques-Louis David’s General Bonaparte (ca. 1797-98) for having the hair of a “bad teacher.” He liked that David’s Portrait of Gaspar Meyer (1795-96) was “all colored in.” Aptekar repainted the two portraits on adjacent panels and added brightly colored splotches in Nino’s favorite, the Portrait of Gaspar Meyer, which are reminiscent of a child’s imagination. Aptekar wanted to create the impression of “a kid not coloring within the lines.”[12] Nino’s naive interpretation of David’s works is not within the bounds of traditional art criticism, but his perspective is the one that brings new color, literally and figuratively, to the paintings.

After a walk through Aptekar’s “Look Again” exhibition, viewers leave with a new awareness of what they can bring to a piece of art, whether it is a childhood memory, a witty catch phrase, or a thoughtful question. In a fictitious letter to Rembrandt written for an issue of Art Journal, Aptekar writes of the master’s paintings, “it is our pleasure and responsibility to create their meaning.”[13] This is a sentiment he applies to all art. Aptekar’s paintings provide gallery-goers with an opportunity to see how art can reflect and even grow from their personal responses, if one simply takes the time to look again.

Emily Swalec ’14 is from West Boylston, Massachusetts, and is majoring in art history and psychology. She is a student in ARTH 340, Postwar and Contemporary Art (1945-2012) for which she wrote this exhibition review as a course project.

[1] Ken Aptekar, “Objecting to Objects: Notes of the Re-Painter,” Artist Lecture, Wheaton College, February 8, 2012.

[2] David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 429-430.

[3] Ken Aptekar, interview by students of Postwar and Contemporary Art, Wheaton College, February 29, 2012.

[4] Ken Aptekar, “Objecting to Objects.”

[5] Terrie Sultan, “Ken Aptekar: Talking to Pictures,” in Ken Aptekar: Talking to Pictures (Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1997), 4.

[6] Ken Aptekar, “Objecting to Objects.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ken Aptekar, interview by students of Postwar and Contemporary Art. Wheaton College, February 29, 2012.

[10] Mieke Bal, “Larger than Life: Reading the Corcoran Collection, in Ken Aptekar: Talking to Pictures (Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1997), 5.

[11] Ken Aptekar, interview by students of Postwar and Contemporary Art.

[12] Ken Aptekar, interview by students of Postwar and Contemporary Art.

[13] Gerald Silk, “Reframes and Refrains: Artists Rethink Art History,” Art Journal 54, no. 3(Autumn, 1995): 13.

Images (top to bottom): Author Emily Swalec ’14; Ken Aptekar, “I’m Six Years Old and Hiding Behind My Hands” (1998); Ken Aptekar, “A Reason to Wake Up” (2005); Ken Aptekar, “Portrait of Nino Alcock-Boselli” (2010).

-

Categories:

- Art