Why We Should Take Advertisements Seriously

By John Grady

Advertisements are important social and cultural documents. A representative sample often reflects a society’s concerns and values as accurately as well-executed surveys do. But how is this possible? How could images designed by people who don’t know, or haven’t talked to, us — and who are completely self-interested to boot – possibly reflect our innermost thoughts and feelings? Figuring out how exercises in persuasion by self-interested advertisers somehow manage to create reliable indicators of public sentiment has puzzled social scientists for a long time. Fortunately, it looks like the new social media may provide a key to solving that puzzle.

Here’s how the advertising process works. Advertisers hire talented people to promote their products in attractive and engaging ways. After a long design and testing period, they launch their appeals at targeted populations (called demographics) through selected media: print, billboards, television and increasingly, the Internet. At this point, advertisements are pumped through the media into the massive torrent of communications that characterize everyday life.

It’s not easy to get people’s attention. Advertisers compete not only with other advertisers but also the zillion other communiqués that people receive in a single day. These include pop songs, newspapers, television programming, and the innumerable conversations we have with family, friends, acquaintances and all those others whose paths we cross. Finally, advertisers have to infiltrate the incessant personal monologues that occupy our everyday consciousness.

Over the last century advertisers have been busily devising ways to cajole consumers into not turning off their messages (both literally and figuratively). Today the industry focuses increasingly on producing story telling gems that engage the audience with wit, humor and pathos. In short, a form of public entertainment – art, if you will — has replaced the hard sales pitch.

The goal of an advertising campaign, therefore, is to convince consumers to view the commercial as an answer to their inchoate preoccupations: will I — and mine — be better off, happier, healthier, more attractive, more popular, more enlightened, with this product or service than without it. Usually, however, the best that an advertiser can hope for is to have an audience enjoy the people and events portrayed in the advertisement and pray that this positive feeling will somehow attach itself to the product being hawked. If advertisements do engage people’s attention in this fashion then this would explain why it would be possible for researchers to view advertisements as reliable indicators of what concerns and preoccupies a population. But do we have any evidence that the public is actually engaged by these offerings?

Camp Gyno is a commercial released in 2013 by Helloflo, a service that delivers a kit of tampons, pads and candies to young girls who have reached menarche. CNN’s Kelly Wallace describes the ad:

“In it, a tween is the first girl to get her period at camp, what she calls her ‘red badge of courage’, and proudly sets out to teach her pals about this milestone. ‘For these campers, I was their Joan of Arc,’ she says. ‘It’s like I’m Joan, and their vag is the arc.’

“Did she just say ‘vag’ in an ad?”

In the space of a minute and a half our young protagonist rises from the lower ranks of the camp pecking order to the heights of power as the “Camp Gyno” — channeling the persona of a Marine Corps drill instructor in her quest — only to fall from grace as packages of Helloflo mysteriously arrive on campers’ cabin doorsteps.

The high point of the ad is a scene (figure 1) where our heroine demonstrates menstruation to two astonished camp mates using a Dora the Explorer doll and a squeeze bottle of ketchup.

Kelly Wallace continues:

“I wasn’t setting out with this incredible feminist agenda,” said Naama Bloom, the creator of the ad and founder of a company called HelloFlo, which offers women a subscription service for monthly supplies of tampons and pads, and period starter kits for young girls.

“I just wanted to talk the way women talked and the way I talk and the way I am teaching my daughter to talk,” said the mom of two.”

In a personal communication, Blook reported to me that her start-up couldn’t afford an ad campaign on television. Instead, she gambled that on YouTube she could connect with other women – moms and tweens — about their concerns. And, boy, did she! The commercial went viral and within a week it had more than five million hits and is still climbing. As of July 2017, more than 12 million hits.

Even more interesting than the ad itself — and the wide media coverage it has received — has been the response on the web. The “likes” outnumber the “dislikes” by 13 to 1. Camp Gyno has also become fodder for discussion on women’s blogs, mini-documentary treatments and other forums on YouTube and the like. The overwhelming majority of discussants approves of the frank talk about a subject that is often discussed publicly – and invariably advertised – only in euphemisms. Nevertheless, a number of women question whether it is doing girls a disservice by romanticizing having your period and if the product itself — the Helloflo service — is all that useful.

HelloFlo has since released other video promotions on the same theme and that are even more over the top. in June 2014, a tweener’s parents organize a First Moon Party to celebrate their mortified daughter’s imminent first menses. Three year’s later First Moon Party has received over 41 million hits and the likes outscore the dislikes 18 to 1.

Luv’s, which makes diapers and baby wipes, has produced at least four commercials over the last year or so in its FIRST KID… SECOND KID campaign. These are gently amusing television spots that compare the comfortable competence of an experienced mom to her earlier, more anxious, self. Most of them have received around a hundred thousand hits. But only the breastfeeding ad went truly viral (figure 2).

Two million hits, and a “like” to “dislike” ratio of 20 to 1, this ad has nevertheless triggered off a debate about breastfeeding that is far more contentious than Camp Gyno’s treatment of menstruation. Should women breastfeed in public or only in private? Is it a natural or disgusting act? Those who comment – and there are a great many — manage to be offended – or offended at someone else’s being offended — by questions like these.

For sociologists these comments on the web confirm an impression that we’ve had for some time but didn’t have the data to prove. Advertising’s power is due not so much to what it might be shoveling into each of our brains but more to its ability to spark group awareness and interaction through countless, and until now most often anonymous, conversations. Today, the emergence of the new social media enables us to trace how advertisements actually enter into public discourse.

Advertisements are not only designed to promote commodities but also constitute moral fables that model what kinds of people we should become and how we should treat each other. Even when these fictions are ironic, advertisers invariably construct an imaginary social order that they hope we will respond to favorably. Because the world is always changing and because advertisers need to make their messages especially noticeable, they often deliberately transgress established moral boundaries by imagining how social mores and cultural styles might be altered in sometimes-unconventional ways. If the content and style of their advertisements stray too far from deeply held beliefs and norms, the public – or at least some very vocal elements in it – will be outraged. Conversely, if advertisers dramatize what many have been feeling for some time but have neither had the imagination or courage to articulate, then the public will respond favorably, and attitudes may change surprisingly quickly.

The HelloFlo and Luv’s advertisements address issues about the female body and its functions that have either been taboo in polite society, or treated euphemistically. What the advertisements are saying is that a society that has a hard time accepting frank depictions and conversations about breastfeeding and menstruation is one that demeans the full range of women’s experience (After all, hasn’t each of our lives been announced by a missed period!). Bringing the discussion of these aspects of female biology into the open, therefore, may not only change how women are seen in contemporary society, but also how comfortable women may become in experiencing their bodies. Such a change would build, of course, on the long struggle for women’s rights that has been fought with increasing success over the last half century.

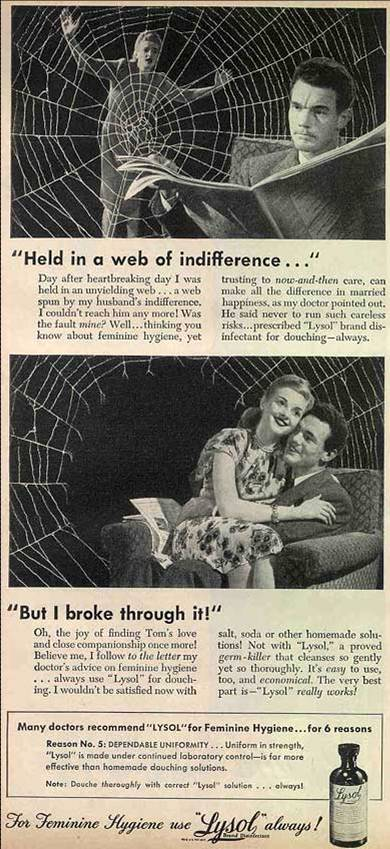

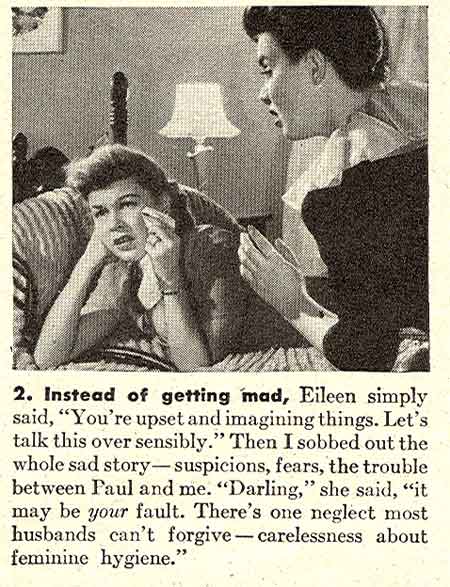

Increased frankness in advertising’s treatment of women’s concerns and in dramatizing the actual ways that women talk and the ways that some are teaching their daughters to talk are, therefore, markers of social change, and in time more conventional depictions will come to be seen as priggish, silly or worse as these mid-twentieth century ads about feminine hygiene (figures 3 and 4) strike us today.

Figure 3. Lysol advertisement (c. 1940) for feminine hygiene

Themes in advertising often anticipate emerging shifts in public opinion, which may not yet have been articulated publicly nor noticed by commentators. Can advertising influence the direction of that change? Certainly! But only when large groups of people actively choose to incorporate advertisers’ appeals into the ways they make sense of their own lives and relationships. The evidence from YouTube is that this is an extremely dynamic process. Stay tuned!

-

Categories:

- Sociology