Unpacking the Food of Food Assistance

By Delia MacLaughlin, Class of 2022

Delia is a Senior at Wheaton College from Columbus, OH. She will be graduating with a double major in Sociology and Environmental Science.

Nominating faculty member: Professor Justin Schupp

In the spring of 2020, missing gardening with my WheaFarm friends and curious about melding my sociological interest in food justice with scientific questions about environmental sustainability, I began volunteering at a local food pantry structured like a fresh market. Concurrently, I was working for a compost collection company. I was horrified by the number of garbage bins I would fill with compostable food waste dropped off at a farmers’ market booth. There was a stark duality between this and the seemingly never-ending lines of cars picking up food at the pantry that pantry employees noted as unprecedented.

My thesis research originally set out to explore the consumption rituals of food assistance users. I helped pack boxes of beautiful fresh produce at pantries for pantry clients, but what happened when they took it home? How were they preparing it? With whom were they eating? How did this differ from the compost service subscribers who bought food to compost pounds and pounds of it— and how did pantry clients perceive these differences?

When I began the data collection process, the COVID-19 Omicron variant was surfacing in Columbus and reinforcing the literal and conceptual social distance between pantry employees and pantry users. One of my employee respondents, when explaining the experiences of her pantry clients living in poverty, noted that they deal with:

“Decision fatigue every day. Rent, utilities, childcare, transportation, food. So what other issues do we bombard people with and then just expect them to navigate it?”

Because of the extra burden of the pandemic, my intended population was hard to reach because of a crunch in their available time, energy, and resources. It was too hard to “snowball sample,” a recruitment method where pantry staff could theoretically aid in pointing me to clients who might have interesting perspectives. With help from my advisor Professor Justin Schupp, I pivoted my research to focus on a population that I knew I could access. I began heavily recruiting employees of pantries in Columbus. The primary food bank in Columbus, the Mid-Ohio Food Collective, had been popping up in my interviews, so I interviewed staff members there as well.

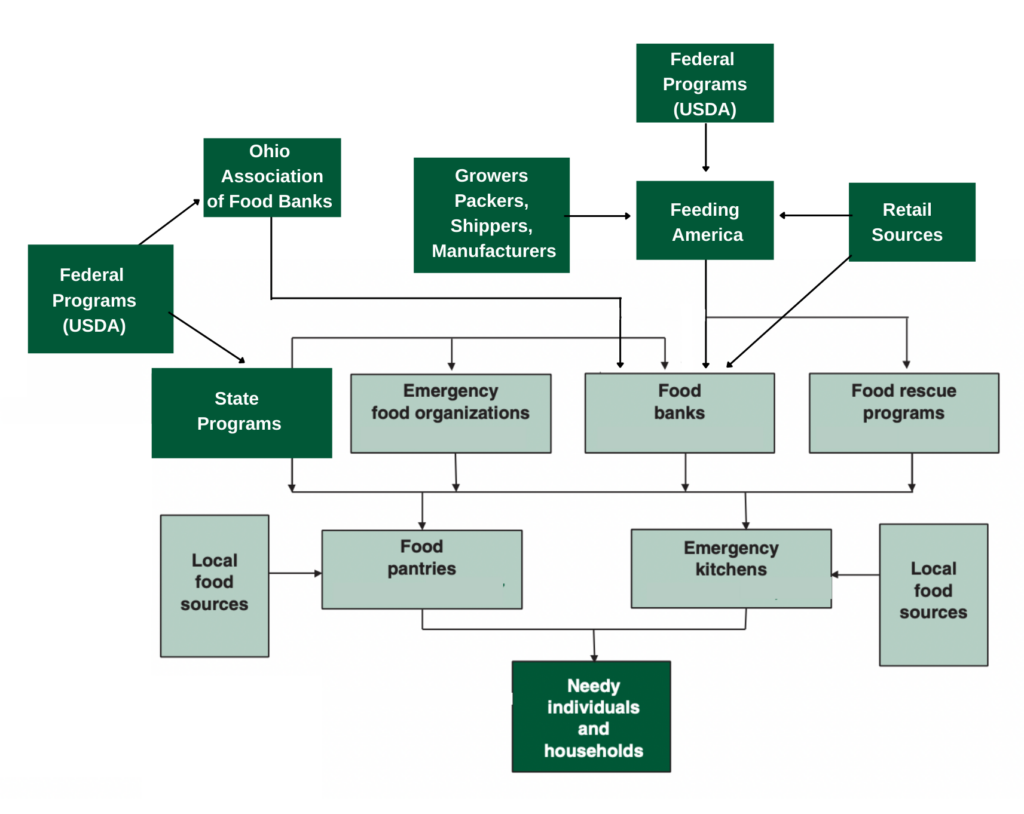

The chart below illustrates the complexity of the system as described by employees working at food pantries and at Mid-Ohio. As more interviews were conducted, I found that the food assistance system that I had myself volunteered in was more nuanced than originally understood.

In my Sociology honors thesis titled “Unpacking the Food in Food Assistance,” I begin to work through this system to trace the path that food takes from production to distribution at food pantries. I tailored my interviews to fit the following questions: How do food pantries consciously or unconsciously constraint pantry clients through their structure and operation? How does the institutionalization of the U.S. food assistance system impact food pantries on a local level? How do micro-level interactions between pantry organizations and other agents in the Columbus food assistance network impact the food that is ultimately distributed to pantry clients?

Using a theoretical framework of Max Weber’s bureaucracy (1922) and fundamental social theorist Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of taste and capital (1984; 1985) I found social distinctions and boundaries drawn within a bureaucratic U.S. food assistance system. These distinctions and boundaries have strong correlation to neoliberal ideology. A summary of the impact of neoliberal ideology can be seen as defining people in poverty as irresponsible because they are not economically self-sufficient. Clearly, this is not a just perspective when providing aid to people in poverty.

While the pantry workers I interviewed did not assert that they held this attitude, I saw the effect of neoliberalism in the form of poverty governance and stigma. Federal organizations like the USDA imparted rules and regulations all the way down the food system to local pantries. This, for example, took the form of collecting massive amounts of data on people using food assistance to confirm their (lack of) resources and to surveil them.

I also saw governance as restriction of the personal agency of the clients, which I conceptualized as their ability to choose what to eat. This took place when, for example, pantries handed out pre-packed boxes of food instead of allowing clients to “shop” for themselves in a pantry. It also looked like pantries assigning a volunteer to monitor a client if they could shop to ensure that they were not taking beyond the allotted items. Pantries even made decisions about what food items made it to pantry shelves. Juice, for example, was a hot debate— some pantry employees felt it was too sugary and unhealthy for clients while others did not want to regulate a client’s ability to choose that food.

My work is novel in that I looked at a local food assistance network to trace the influence of neoliberal ideology throughout an entire national system. I connected this to tangible examples promoting poverty governance and stigmatization of poverty that fundamentally shapes what food is donated and how pantries are modeled. In applying the influence of neoliberalism on the food assistance system, I also developed a new understanding of a concept of food governance.

Because so much of the food that ends up at a pantry is from the USDA in the form of subsidized commodities bought in excess from U.S. farmers, I argued that the State needs to satisfy the agricultural sources where food comes from through food governance. In doing this, they created a food assistance system that creates model, neoliberal consumers out of food-insecure people. I saw this when I saw the rules and regulations on pantry operations that food pantries followed and the food bank had to enforce. I also saw this when I analyzed my pantry employee respondents discussing how they encourage their clients to work with

My work did reveal an avenue through which to combat this notion of food governance, and it can happen through the scale on which I collected data. The local food bank in conjunction with food pantries are trying to achieve food sovereignty while pushing the Columbus food assistance system towards adopting a food justice ideology. This looked like beginning a new urban farm operation, hiring food insecure people to become farmers and grow food to source local pantries. It also looked like humanizing the food pantry experience. One respondent identified that they sourced local, fresh-baked donuts that other pantries would consider unhealthy:

“If the only thing that you’re eating is donuts, that is more sugar than a human needs […] But also sometimes you just want a donut. And these are like, the best, baked that day, no preservatives, like they’re fabulous. And if it is possible to share that bounty of deliciousness, that’s a different kind of healthy food. That is a different kind of meaning that people get from the food they eat, and that matters too.”

While my work was not able to put a focus on the people actually utilizing food assistance, I was able to highlight tangible and ideological constraints on work of local organizations to address food insecurity. I was also able to highlight grounds of contention with the overarching federal system that prioritized community, neighbor-to-neighbor connections. I propose that promoting local food sovereignty can diminish the heavy reliance on donated government food along with governance, rules, and regulation that comes with it. In doing so, we can create a local system of food assistance that has greater flexibility in providing food that is nutritious, healthy, good, and useful for people who need it.

-

Categories:

- Academic Festival

- Sociology