Debating the Electoral College

This year marks the 237th anniversary of the signing of the U.S. Constitution. As we approach a significant presidential election, Constitution Day is a reminder of the country’s founding principles of liberty, justice, equality and democracy.

In the following essay, Bradford H. Bishop, associate professor of Political Science, examines the American electoral process and its effectiveness and challenges in ensuring fair and equal representation.

By Bradford H. Bishop, Associate Professor

Department of Political Science

With the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election fast approaching, it is important to understand the unique way that Americans elect a president. Elections are a deceptively simple process—candidates compete for election to an office, eligible voters cast ballots registering their choices, we compile the results, and the person with the most votes wins. However, when we examine the electoral process more closely, difficult questions arise. For example, should we require that the winner of an election receive a majority of the vote? Without this requirement, it is possible a winner could be elected with a small share of the vote that nonetheless represents a plurality of the total votes cast. More concerning is the possibility that, in an election with numerous competitors, the winner could be a person with a small but solid base of support who is disliked by the majority of voters. Another difficult question concerns the distribution of support. Is it acceptable for an election winner to have a narrow, regional base of support or should we want the winner to be assemble a coalition that extends across the country? This concern animated many of the thinkers of the founding generation, including the nation’s first president George Washington, who warned about the dangers of geographical division in his farewell address of 1796.

Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution establishes the framework for the controversial process used to elect a president. The first thing to appreciate about the system is that most of the rules and processes are determined by the states. For example, states are broadly free to determine eligibility for voting and develop processes for establishing and verifying eligibility. States also control the mode of casting votes in an election, such as whether ballots are paper and marked with a pencil, whether they are registered electronically, or whether they are cast by mail. Under the constitution, a presidential election winner is determined not by computing the number of total votes that are cast across the country (the “popular vote”) but by computing the number of votes a candidate receives from electors that are appointed by the states (the “Electoral College”). States are assigned a share of electors based upon the total number of representatives they elect to the U.S. Congress. Massachusetts, for example, has 2 U.S. Senate seats and 9 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Thus, in a presidential election, the state chooses 11 members to serve in the Electoral College. Once chosen, the electors cast ballots for the offices of president and vice president. The winner of the election is the candidate who receives a majority of the votes cast in the Electoral College; in today’s elections, the winner must receive at least 270 electoral votes.

Most of the framers of the constitution initially conceived of the Electoral College as a mechanism for ensuring that the selection of a president would be made by an enlightened and worldly subset of the public. The constitution allows states to choose the mechanism by which electors are chosen. Though states used a variety of different methods of choosing electors in the early years of the republic, they eventually decided to choose electors through a popular election. Over time, and particularly as the party system developed in the country, it became evident to the public that different electors were likely to vote for particular presidential contenders. Thus, a vote for a particular elector evolved into an indirect, proxy vote for a candidate the voter preferred. Over time, most states changed their ballots to reflect this reality, allowing voters to choose between electors who were “pledged” to vote for a particular presidential candidate. The 2020 ballot in Massachusetts, for instance, titled the presidential choice as “Electors of President and Vice President” and then provided the last names of the presidential and vice presidential candidates for each party team (e.g., Biden and Harris, Trump and Pence). As Biden and Harris won the popular vote in Massachusetts in 2020, the slate of 11 electors that had pledged to vote Biden/ Harris was elected to represent the state at the Electoral College.

As noted above, states are free to allocate their electoral votes using a variety of different methods. Most states—48 of them, to be precise—have chosen to use a “winner take all” method of awarding electors. Under this system, the presidential ticket that wins a plurality of the state’s popular vote is rewarded with the state’s entire allotment of electors. So, for example, if Biden/ Harris had defeated Trump/ Pence by a single vote in Massachusetts in 2020, they would have been supported by all 11 electors in the 2020 Electoral College. Two states have chosen a different method of allocating electors. Maine and Nebraska use the same alternative system: they award two of their electors to the overall winner of the state popular vote, and then they award their remaining electors to the popular vote winner within each of their congressional districts. So, in Maine in 2020, Biden/ Harris won the overall state popular vote and won 2 electoral votes as a result. They also won the popular vote in the state’s southern congressional district, and won an additional electoral vote for that victory. However, the Trump/ Pence ticket won a plurality of the vote in Maine’s northern congressional district. Therefore, of Maine’s allotment of 4 electoral votes, Biden/ Harris won 3 while Trump/ Pence won 1. In the same election, Trump/ Pence won 4 of Nebraska’s 5 electoral votes, while Biden/ Harris were awarded with 1 electoral vote in Nebraska by winning the state’s Omaha-based congressional district.

This system for electing presidents has persisted for more than 200 years, though it was modified by the 12th Amendment in 1804 and by the 20th Amendment in 1933. It has many critics. When we discuss the Electoral College in my Introduction to American Politics course, most of my students advocate for replacing it. Their views are mirrored by the U.S. public; a 2023 Pew survey found that 63% of respondents favored replacing the Electoral College with a system that ensures “…the candidate who receives the most votes wins.” Below, I summarize the criticisms of the system I hear most often.

1. Sometimes the winner of the popular vote does not win a majority in the Electoral College. Because all 50 states eventually decided to choose their electors through a popular election, in each presidential election we are able to calculate the total number of votes cast for each presidential ticket. In four elections—1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016—the candidate who won a majority of votes in the Electoral College garnered fewer overall votes than one of their competitors. For instance, in 2016 Hillary Clinton (D) received nearly 3 million more votes than Donald Trump (R), but Trump was elected president when he defeated her in the Electoral College by a count of 304-227. Results like this strike many people as unfair, as it violates their abstract conception of the purpose of an election, namely that the candidate who wins the most votes should be elected. It’s worth noting, however, that in today’s politics both major party candidates develop strategies that are designed to win the Electoral College, not the popular vote. Thus, the popular vote we observe in our elections is not necessarily the result we would see if the candidates were actively attempting to win an overall popular majority. Donald Trump, for instance, would almost certainly have spent considerable time attempting to win votes in populous states such as California in order to increase his vote share. Under the current system, it would be irrational for candidates to campaign for votes in states they are certain to lose, such as California in the case of Trump. For this reason, it is hard to interpret exactly what the popular vote means, and we should not necessarily treat it as an overall measure of the candidates’ relative levels of support in the country.

2. The Electoral College causes major party campaigns to ignore most of the states. As any observer of presidential elections in Massachusetts is aware, the major party candidates rarely make appearances in uncompetitive states. The Bay State has been safe Democratic territory for more than a generation, as Ronald Reagan was the last Republican to win Massachusetts back in 1984. Because Massachusetts so consistently favors Democratic candidates, both major party candidates are reluctant to invest any resources into winning it. For Republicans, the state is considered a lost cause, so every dollar spent in a campaign here is seen as a wasted investment. The Democrats, who expect to win the state regardless of whether they campaign here, are more likely to redirect resources into states where the outcome is uncertain.

For these reasons, in most elections the campaign is focused on a handful of states that are plausibly winnable for either party’s presidential ticket. In these states, the “battleground states,” both major party campaigns will flood the airwaves with advertising and make numerous in-person appearances to attract attention and rally support. The vast majority of both parties’ campaign funds will be spent in these few states, and in most years, the ticket that wins the competitive states is likely to win a majority in the Electoral College. In 2024, there could be as few as 7 states that both major party campaigns consider to be “battleground” states, meaning that the most intense campaign activity could be experienced by the smallest number of Americans in decades.

Many people object to this limited geographical pattern of campaign attention that is incentivized by the Electoral College. A president governs on behalf of the citizens of all 50 states, and many are troubled by the absence of nationwide campaign activity. Why should Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Georgia play such an outsized role in determining the outcome of an election? After all, the citizens of those states should not be considered more important than the citizens of less competitive states. It is worth appreciating, however, that if the Electoral College were to be replaced by a contest focused on maximizing nationwide vote share, campaign behavior could change substantially. Rather than focusing on winning competitive states, campaigns might focus attention on politically competitive or “swing” demographics, ignoring cities or rural areas. Or, the campaigns could invest resources more narrowly in competitive cities, ignoring population centers like Boston which tilts heavily toward the Democrats. Overall, it is hard to predict how campaigns would respond to a system that replaced the Electoral College, and it is not obvious that people would prefer the change.

3. Faithless Electors. Although the slate of electors appointed to represent the states in the Electoral College are pledged to support a presidential ticket, they are technically free to cast ballots for anyone. In many elections, a handful of electors have chosen to do just that. In 2016, for example, seven electors cast ballots for someone other than the candidate they had pledged to support. Three Washington state electors pledged to support the Clinton/ Kaine ticket chose former Secretary of State Colin Powell instead, while a fourth elector defected to Faith Spotted Eagle, a Native American activist from South Dakota.

This feature of the Electoral College raises concerns from many observers of American politics who worry that, in a competitive election, a small number of electors could overturn the result of a presidential election. Particularly in a closely divided nation such as the one we observe in 2024, it is possible that a presidential candidate could win an election by a small number of electoral votes. Such an outcome could be threatened by so-called “faithless electors.” In response to these concerns, some states have adopted punitive laws that impose fines on electors who vote for a ticket other than the one they pledged to support. The U.S. Supreme Court has so far ruled that such laws do not violate the constitution, so they may represent a solution to this problem.

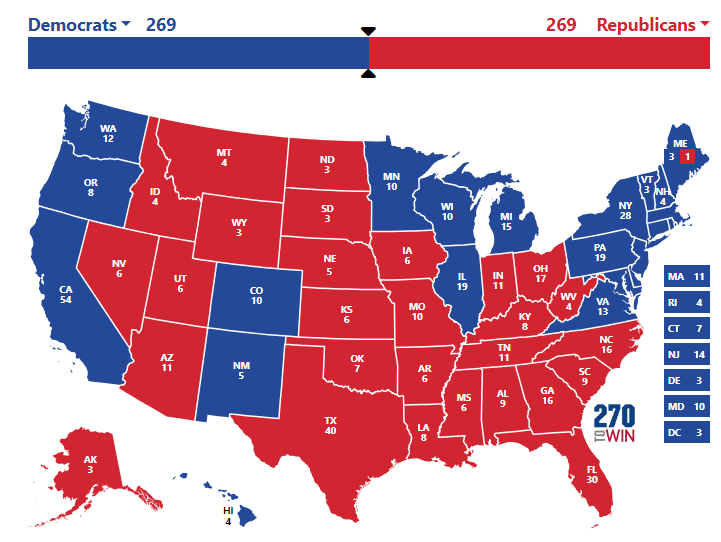

4. Concerns about procedures used when no candidate wins an Electoral College majority. To be elected, a presidential candidate must win an absolute majority of the electoral votes. However, there are a number of ways an election outcome would not result in any candidate winning a majority. First, if there is a competitive third-party candidate who is able to win a majority in several states, the most successful major party candidate may fail to assemble an Electoral College majority. Second, even in the absence of a competitive third-party presidential candidate, there are plausible combinations of states that could result in an Electoral College tie of 269 electoral votes for each presidential ticket. The attached map presents one such scenario.

Figure 1: A hypothetical 2024 presidential outcome that results in an Electoral College tie.

In the event of a tie, the U.S. House of Representatives is tasked with choosing the election winner. As the entirety of the membership of that chamber is elected every two years, we won’t know the partisan composition of the U.S. House until after Election Day, so it is hard to predict which presidential candidate would be favored in this scenario. However, there is an additional wrinkle: the constitution requires each state’s U.S. House delegation to cast a single vote for the presidency. This creates potential problems for states with an even number of U.S. House members. Consider Maine, which could theoretically elect a Republican in its northern district and a Democrat in its southern District. In the event of a tie in the Electoral College, would these members be able to agree on how their state would vote? If not, it is possible that when adding up the votes for president, the Maine delegation might simply abstain from voting. For this reason, the ultimate outcome of a tied Electoral College vote is very hard to predict, and the arbitrary nature of the outcome is worrisome for many observers of the U.S. political system.

The Electoral College has always had its defenders, and it continues to have advocates up to the present day. Below, I present a few of the arguments they make.

1. The Electoral College reinforces a federal system. Most people in the 18th Century considered state government to be a more important source of political power than the national government. For this reason, the constitution limits the authority of the federal government and reserves a significant amount of power to the states. As many of us remember, during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, governments imposed unprecedented restrictions on commerce and public life in general, limiting business activity and requiring people to wear masks in public places. The vast majority of these policies were enacted by the states, wielding what constitutional scholars call the “police power.” There are many advocates for such a system, arguing that it deepens democracy by allowing regional majorities to be governed by more policies that conform to their preferences. The Electoral College system reinforces the significance and relevance of states by forcing campaigns to interact with the states as distinct political entities. When campaigns attempt to win a state’s electoral votes, the system leads them to consider the distinct political context of each state.

More broadly, advocates of federalism worry that a shift in the focus of campaigns toward a popular vote could result in a regionally concentrated popular vote winner. As noted above, geographical divisions have worried observers of American politics for centuries. Consider the following, admittedly unlikely, hypothetical scenario. Suppose a candidate were to win the two most populated states in the country, California and Texas, by a lopsided 75%-25% majority. But suppose the same candidate lost each of the other 48 states and the District of Columbia by a 45%-55% margin. Using 2023 estimates of eligible voters in each state, and if we optimistically assume 70% of them turn out to vote, the candidate would win the popular vote by about 4 million votes while losing the Electoral College by a 444-94 margin. Should the candidate winning the popular vote become president with this pattern of support? Advocates of a federal system would say no, arguing that a presidential ticket must assemble a geographically diverse coalition in addition to winning a large share of the vote.

2. The Electoral College reinforces the two-party system. One of the most distinct features of the U.S. politics is its longstanding two-party competitive system. Since the Civil War, the Democratic and Republican parties have dominated both presidential and congressional elections, with some rare and short-lived instances when third parties have disrupted this pattern. The reasons why these two parties have been so dominant for so long are numerous and complex. However, the primary factor is our electoral institutions for both the U.S. Congress and the presidency. To fill these government positions we hold elections that produce a single winner. And in most cases, the winner is determined by plurality—the person who wins the largest number of votes fills the seat. Political scientists have observed that these systems tend to produce two party competition. This is because candidates and parties who finish in second place receive no representation in government; the winner gets the seat and all other competitors receive nothing. Recognizing that there is no prize for second place in the American system, the losers in an election have powerful incentives to form a coalition that can compete with the winner in the next election. Voters are also aware of the futility of voting for third-party or independent candidates that have little chance of winning an election and are reluctant to “waste” their vote on a lost cause.

The same logic applies to presidential elections because of the “winner take all” feature of the way states allocate their electoral votes. Third-party candidates have little chance of winning an outright plurality or majority in any given state, so the system creates incentives for coalition-building and ultimately the formation of two large parties who compete for each state’s electoral votes.

The two-party system has its critics, many of whom argue that voters should have the opportunity to select between a wider variety of parties who provide a better match for voters’ specific views. Supporters, however, argue that a two-party system promotes moderate politics. As political thinkers from Aristotle to the economist Anthony Downs have recognized, in a two-party system, candidates have powerful incentives to appeal to voters in the center of the ideological spectrum. The centripetal forces of the system can be seen in the pro-choice position on abortion taken by Republican Donald Trump in recent weeks or the increasingly conservative stance on immigration articulated by Kamala Harris following her nomination by the Democratic Party. Because the Electoral College reinforces the two-party system, its defenders argue that it promotes substantially more moderate politics than what we would observe in a multiparty system.

Critics of the Electoral College have proposed numerous solutions for replacing the system—each of which has controversial features. The vast majority of these reform ideas would require a rewrite of the presidential election system in the form of a constitutional amendment. These types of changes are rare in the United States because they require super-majority support across the country in order to be enacted. Until there is wide consensus that the Electoral College should be replaced, and the public converges on a particular solution, the system is likely to persist well into the future.

-

Categories:

- Academics

- Political Science