Navigating Identity Abroad

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow mindedness.” Mark Twain

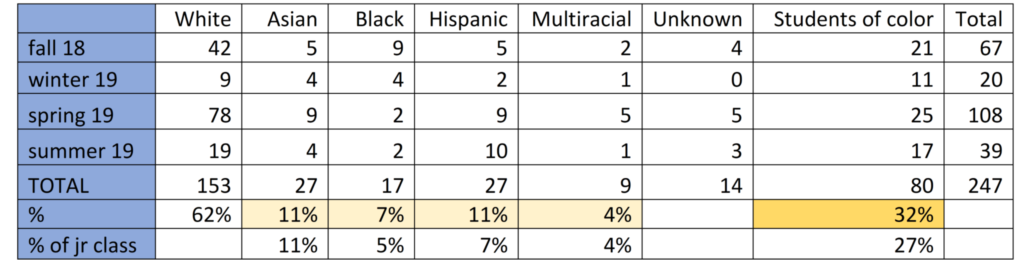

In 2018-2019 32% of Wheaton students who studied abroad were students of color. This is compared to the 27% of the junior class in 2018 who identified as students of color.

We should be proud of this percentage. It is a number that most institutions strive to increase. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education released an article discussing this just today. Yet we are realizing that along with sending more diverse students abroad we must also improve our support for these students. Our diverse students are encountering challenges that students in the past were not encountering. We are now recognizing that “the old models of study abroad— which included homogeneous U.S. student populations, relative lack of charged heritage relations with receiving countries, lack of “racial” problematics between the visitors and hosts, general economic equality, and lack of conditioning global informatic frameworks—decreasingly work today.” (Landau, 2015, p.55 )

Fortunately at Wheaton, our small, tight-knit community makes for easy collaboration between the Center for Global Education and offices such as The Marshall Center for Intercultural Learning, the Filene Center and our students themselves to address these topics. Within the parameters of our new curriculum there will be even more opportunities for teaching and learning associated with all aspects of study abroad. Our increased number of faculty-led short-term study abroad programs attract particularly diverse participants. These are experiences where students usually bond with the group and the faculty member and experiences are often shared. Faculty can include moments for reflection and discussion in their course that help students to process what they are seeing and experiencing. Students are often forced to contemplate their identities while abroad. When asked in a recent survey “Did you notice any differing attitudes towards any particular groups (perhaps based on gender, religion, race, ability) while in your host country or a country you visited while abroad?” here is what some of our students said:

“European countries are often romanticized by white Americans without taking into account the roles that intersectionality and marginalization play. I was abroad in Denmark… and that was very prevalent. I’ve had a phenomenal experience however I was hyper self-aware of the nuances that many of my peers didn’t see. Homogenous countries are not as inclusive or culturally competent as the narrative often makes it out to be.” (current Wheaton student)

Johnetta Cole, President of HBCU Spelman College, has commented that when asked why many students of color do not study abroad “the response of many of our students is that they know and, on some level, understand American racism, but why venture into foreign variations on that everyday theme?” (Anderson, 1996, p.320)

In my own experience directing study abroad programs in various parts of Africa, I struggled to facilitate the difficult conversations that came up regularly concerning race and identity.

For example, what do you say to an African American student who runs into your office crying after having the N- word hurled at her by an African man as she was walking down a perfectly safe street in Dakar, Senegal.

Or the student on a program in Cameroon who was asked by a local friend “if things are so bad in for Blacks in America, why don’t you come back to Africa? Why didn’t they come back once slavery was abolished?”

Another phenomenon is that “heritage seekers” often have unrealistic expectations that are not met: “I was hoping to get more of a welcome home type of vibe. In terms of like, Oh, black American, welcome home, this is your home, but I didn’t get any of that. I’ve gotten a lot of welcome but I expected it to be like I was coming back to Africa, like roots, this is where it all began. I haven’t gotten that reception (BAM1).” (Landau, 2015, p.32)

“I made a short film while I was there documenting the experience of being a Greek American in Greece, how I was accepted and at times not.” (current Wheaton student)

In another instance a group of American students studying in South Africa were having a debriefing session about their home-stay experiences. One white student expressed the emotions she was feeling being in the racial minority. She stated that she finally understood how minorities must feel in the United States. Other students who identified as minorities in the US verbally attacked her for this statement.

If experiences such as these are not acknowledged and discussed they are detrimental rather than learning opportunities; sometimes not only for the student affected but for the entire group. In the third scenario it was not only the white student who learned something from this experience, besides to never open her mouth again in discussions of race.

As educators we need to present such situations as a rare opportunity to discuss an issue using a tangible example and perhaps a little distance. In the case of faculty-led programs the faculty member is well positioned to facilitate these discussions for the group in the moment. In other situations, the students may be alone to work through such experiences, so we need to prepare them well beforehand and encourage them to debrief their experiences once they return home.

“What I witnessed personally was that there were differing attitudes towards the Asian population in Australia. There had been exclusion of these people as Australians even though they had lived there their entire lives. The phrase “f*** off we’re full” was also used towards this population both historically and currently.” (current Wheaton student)

In a study conducted by Susan Talburt and Melissa Stewart (1999) which focused on the relations of students’ cultural learning during a 5-week study abroad program in Spain, they discuss an African American student who experienced multiple acts of racism. They observed the “ways Misheila’s race and gender became problematized in the process of her coming to know Spanish culture, how those issues entered the formal class curriculum, and how they affected other students’ perceptions of their positions in the culture [and] encouraged them not to just stay within what they’ve know all their lives, [but] that there is something else out there… Misheila’s account may have pushed some of her classmates to think critically about their own society in ways that would not have been possible in a U.S. classroom. In this unfamiliar space, where an identification was assumed among them as Americans first, the Spaniards who singled Misheila out as different disrupted the “we’re all Americans” bond and forced race into the picture – a picture which may well include White students’ unacknowledged racial positioning. The class discussion was more than just a simple exercise in pointing the finger at perceived Spanish racism. Rather, it hinted at students’ different positionings as male, female, White and Black.” (172)

“I think a good part of my abroad experience was identifying these issues and being able to compare/contrast with the US and other countries.” (current Wheaton student)

Through seemingly negative experiences students can sometimes come to terms with the fact that their way of thinking is not the only way. People who identify as they do don’t always come at issues from the same perspective. And sometimes words they may see as prejudiced or hurtful may not have been intended as they interpreted them. For example, an American LGBTQ+ student visiting a gay rights NGO in Copenhagen was offended when a representative of the association told them their insistence on promoting usage of non-binary pronouns diverted attention from burning issues like health rights and other larger and more important structural problems for LGBTQ+ folks. Another teachable moment.

“Conversations around immigration, gender identity, and interracial relationships came from a different understanding of the world, in my experience.” (current Wheaton student)

It is not only African American students who grapple with unexpected challenges due to their identity abroad. Our goal is to better prepare students for such encounters without scaring them away. We therefore encourage all students to reflect on the different ways they identify as individuals and contemplate the possible implications before embarking on their semester abroad. Here on campus we have implemented several new initiatives. This past fall students from Safe Haus organized an event entitled Gays Go Global which was very well attended. Each semester the CGE facilitates a broader session during our mandatory Pre-Departure Orientation entitled Navigating Your Identity Abroad in which returned study abroad students discuss how aspects of their own identity influenced their experiences abroad, positively, negatively, or simply caused them to pause. We discuss how different social identities can become more or less apparent while abroad. For many students, going abroad allows them the freedom to be more “themselves.” Some students express that they became more self-aware, some students are faced with discrimination or misunderstandings they have never before experienced and find little support in-country.

Some questions we approach in orientation are:

- What is it like to be Asian-American in China?

- Are women’s experiences abroad significantly different than men’s?

- What have LGBTQ+ students’ experiences been like in cultures that are more or less accepting of the queer community?

- What about being Jewish in Germany?

In the end, while seemingly contradictory, if students are sometimes made uncomfortable and we send them home asking more questions than they had when they got on the plane, we’ve done our job.

“I did notice differing attitudes towards particular groups. Amidst the ongoing economic and social conflict in Argentina is a tone that from my perspective I would be considered racist and sexist. With that being said, exposure to these attitudes educates. While it is not something pleasant to interact with, it’s important to learn the root of and try to untangle such social structures.” (current Wheaton student)

Gretchen Young, Dean, Center for Global Education

References

Anderson, K. (1996). Education: Expanding your horizons. Black Enterprise, 26, 318-324.

Landau, J. & Moore, D.C. (2015) Towards Reconciliation in the Motherland: Race, Class, Nationality, Gender, and the Complexities of American Student Presence at the University of Ghana, Legon. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, volume 7 v3, 25-59.

Talburt, S., & Stewart, M., (1999) What’s the Subject of Study Abroad?: Race, Gender, and “Living Culture.” Modern Language Journal 83, 163-175.

-

Categories:

- Center for Global Education

- Parents

- Provost