Best Buds or What?

“Best Buds or What?” By Megan Barnes’18

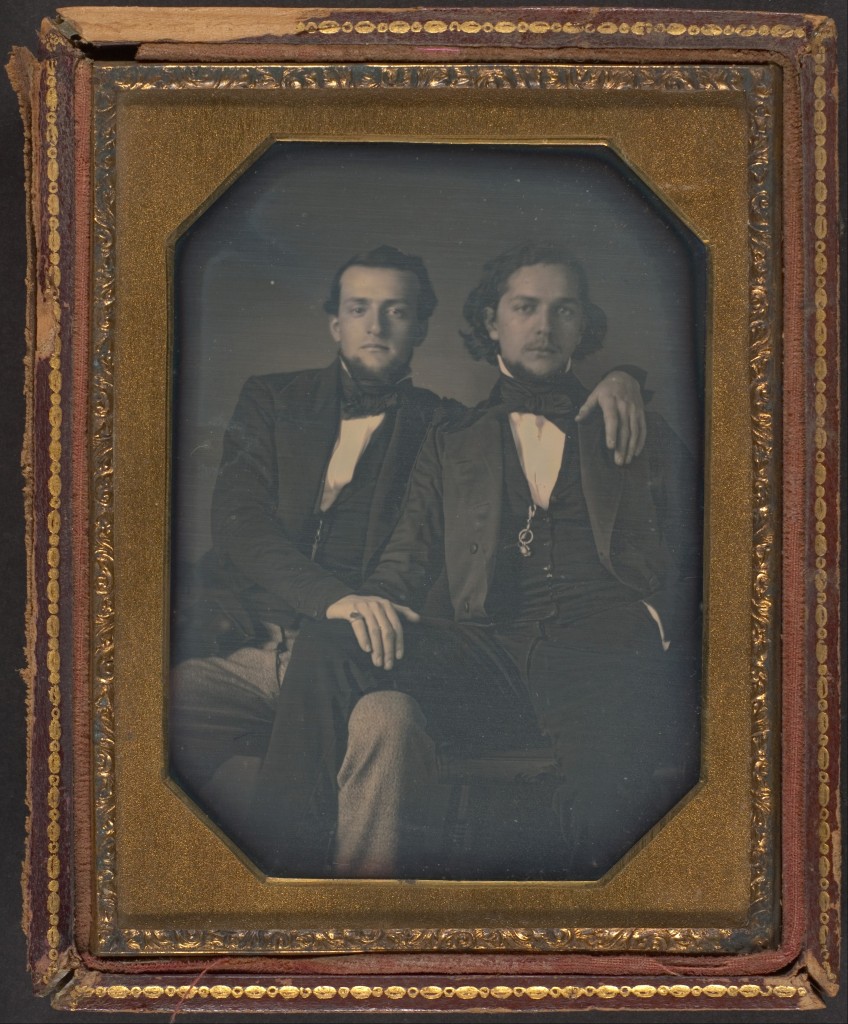

An unidentified photographer made this daguerreotype portraying two young men in the mid nineteenth century, only eleven years after the invention of photography. On first examination, a modern viewer would likely think that these two men were lovers. However, when the photo was made being “homosexual” was not a recognized identity (however maligned) and a limited number of what we might today view as “homosexual acts” were defined as aberrant. Very few people then would dream of assuming that two physically close men were romantically or sexually involved with each other, just as we do not typically presume that an affectionate dog owner would be sexually or romantically involved with their pet.

Had it been an established belief that the same desires and behaviors that occur between a man and woman could also happen between men, then it is likely that the same constraints that regulated how men and women were portrayed together in photographs during this period would militate against any depiction of intimacy between men. Photographers did not generally record displays of romantic affection between men and women. It just wasn’t seemly. Thus, when we look at early photographs of men with clasped hands and intertwined legs, we are not seeing an expression of radical sexuality or romance. Rather, we are witnessing a time when the display of unabashed affection between men was an acceptable practice. Sometime between the mid-nineteenth century and today, however, this changed so that what was once seen as normal became abnormal and unimaginable unless it was intended as a spoof. Historians now believe that what transpired was that people in the late nineteenth century to early twentieth century came to identify homosexuality as not just sinful but also a threat to heterosexuality and came to stigmatize most displays of affection between males as signs of being a homosexual.

Not burdened by the stigma of homosexuality, men of the 19th century enjoyed an expanded emotional and physical closeness with one another. These kinds of bonds were expected and happened largely out of necessity due to contemporary social beliefs and practices. During this period men and women’s social spheres didn’t overlap very much because it was believed that the two sexes were intellectually and emotionally incompatible (save for the realm of sexual and marital relations) and that unregulated and frequent contact between men and women might encourage indecent sexual encounters. The result of these arrangements was the creation of “boys only club” mentality that encompassed the life of a young man in the 1850s, fostering intense and affectionate bonds between men that we very rarely see today and find hard to imagine.

When people started speaking of homosexuality and scientists determined homosexuality to be an “inversion” of heterosexuality — a deviation from the norm and a mental illness — men began developing a kind of homophobia. Fearing they would be labeled as homosexuals, men began distancing themselves from each other both emotionally and physically. As you might expect, the commonly assumed pose featured in this daguerreotype, which photographers would encourage men to perform in their studios — as well as any other gestures of male affection — became entirely unacceptable,

Changes in the early twentieth century created a “perfect storm” of pressures that dramatically changed how masculinity was expressed. Men and women found that social expectations afforded them more opportunities for unregulated contact, whether in the office, where women were beginning to work in close propinquity to males, or in the distractions of the modern metropolis. As is clearly shown in the movies and advertisements of the time, men and women were forced to come to terms with each other’s presence, and this encouraged more social interaction and stimulated sexual attraction. Courting and mating was now increasingly unregulated by older generations and became the responsibility of those who were doing the partnering. Roles had to be improvised and the prospects of success or failure created lots of anxiety, which made the participants susceptible to strictures that promised success in the sexual marketplace. Just what attitudes and practices characterized a real man or a real woman? One easy way to establish a comfortable gender identity was to accentuate “heteronormality”, or complete emotional orientation to the opposite gender. In this context, therefore, homosexuality threatened the bond between man and woman, and it was important not only to define it as aberrant but also to avoid any practices that encouraged emotional openness to the same sex. Among other things, this resulted in the reduction of males’ reliance on each other, and in doing so, gave men even lesser reason to form the kinds of bonds with each other that they had in the past.

With the birth of the stigmatized homosexual identity, we thus see the death of an affectionate freedom captured in this 1850 daguerreotype that is denied to men today. It is hard not to conclude that the erosion of male affection toward each other has come at great cost, not only to the lives of men into the present, but also to women as well.

-

Categories:

- Sociology