African Art at Wheaton College

Wheaton’s Permanent Collection contains fewer than 100 objects that have been identified as African. These include Egyptian Coptic textiles, Ethiopian Orthodox Christian art, an Islamic amulet, drawings by Kenyan artist James Muga, musical instruments from Burkina Faso, and Ghanaian woodcarving tools. In the past few years, endowed funds have enabled the college to acquire five contemporary South African prints and a Tanzanian mask while several individuals have also donated objects. These recent acquisitions of African art and material culture are an example of the collection’s continual growth and development.

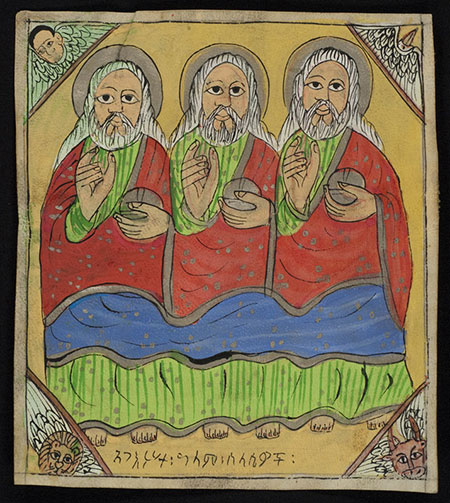

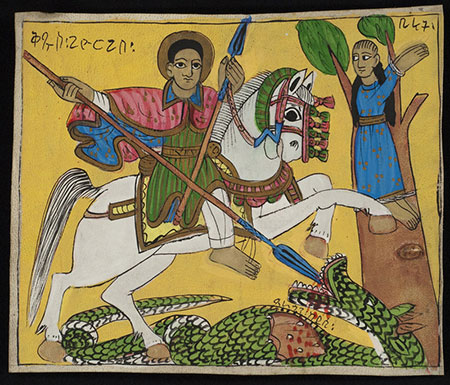

Gammon Collection of Ethiopica

The Gammon Collection of Ethiopica was donated by Ambassador Samuel R. Gammon III, widower of Mary Renwick Gammon, ’48, whose mother and sister were also alumnae. Mrs. Gammon was on the Dean’s List her senior year and ranked 18th in her graduating class. After graduation, she continued to maintain a strong connection to the college, eventually serving on the President’s Commission in the 1990s. As members of the diplomatic corps, the Gammons traveled and collected artwork from around the world, particularly from Ethiopia and Eritrea, two countries they especially loved. Their collection includes ornately carved hand crosses in metal and wood, prayer staff finials, and small paintings that depict various saints revered in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Ambassador Giovinella Gonthier ’72 Collection

Among the most recent donations are African masks given in memory of Ambassador Giovinella Gonthier, ’72. A diplomat and frequent traveler like the Gammons, Gonthier collected African art from several countries including Botswana, Mauritius, Namibia, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. Her husband Roger G. Wilson, Esq. donated nine of his wife’s masks to the college. They are the first African masks in Wheaton’s Permanent Collection.

In their indigenous contexts, such masks are used for various ritual ceremonies including initiations, weddings, births, circumcisions, and funerals. Often, donning a mask immerses the wearer in the spirit world, enabling him – in Africa, masquerades are almost exclusively danced by men – to communicate with the ancestors and other spirits. Certain formal qualities such as hairstyle, headdress, collar, or horns help to identify rank, gender, or other markers of social identity.

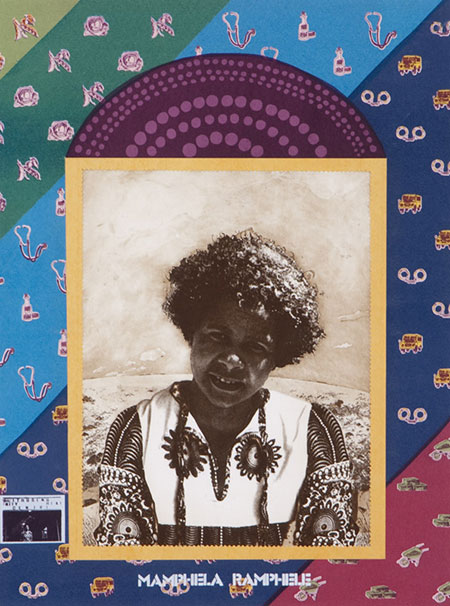

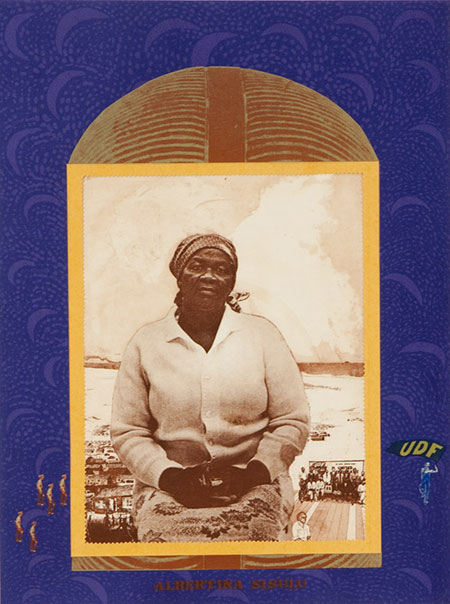

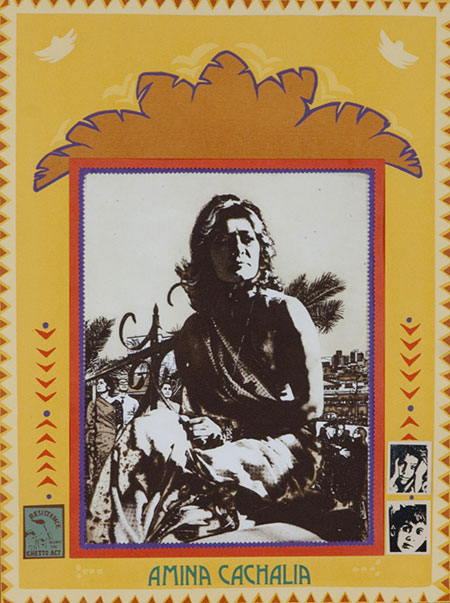

Sue Williamson

Born in Litchfield, England in 1941, Williamson traveled widely to pursue studies in printmaking and photography. Having immigrated to South Africa as a child, Williamson was exposed at an early age to the political struggles of women across the continent. Williamson’s art illustrates her stance against South Africa’s Apartheid-era institutions and her belief Africans must fully confront their past in order to move toward a better future. Most of her works include portraiture, empowering her subjects by providing a vehicle for their voices to be heard. Today, Sue Williamson is an internationally recognized artist whose work is collected by and displayed in major museums around the world. Through the support of the Kenneth C. and Louise McKeon Deemer ’33 Fund, Wheaton was able to acquire three of Williamson’s prints from her 1980s series entitled A Few South Africans.

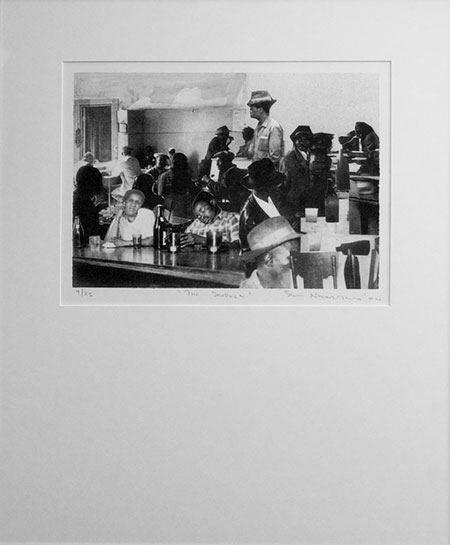

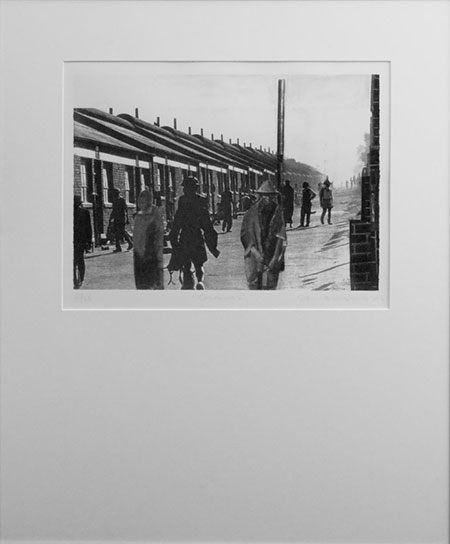

Sam Nhlengethwa

Regarded as one of South Africa’s leading contemporary artists, Sam Nhlengethwa was born in 1955 in a small mining community but grew up in Heidelberg, a larger suburban town located southeast of Johannesburg. Having been raised in and near major urban centers, Nhlengethwa’s work is closely informed by interactions between South Africans and the urban and/or industrial environments in which they live and work. He also looks to the syncopated rhythms of jazz as inspiration for his collages and paintings. Similar to jazz music, Nhlengethwa’s work is distinctly fragmented, defined by the distortion of its tonality and form. His images focus on a variety of subject matter, including the plight of mineworkers, the physical space of contemporary Africa, and life in townships. The Kenneth C. and Louise McKeon Deemer ‘33 Trust was used to acquire two of Nhlengethwa’s collage prints, one depicting a crowded township bar, the other illustrating an industrial scene.

Josh Shade Collection

Josh Shade and his wife Rosa Katz developed their collection of West African objects while living in Burkina Faso. He came to know of Wheaton’s Permanent Collection through Mollie Denhard ’10, who curated Collecting in the Peace Corps: Tangible Memories of the Toughest Job You’ll Ever Love. Shade lent, and later donated, three Burkinabé musical instruments to the exhibition, which highlighted the collections of Returning Peace Corps Volunteers including James Whitney “Whit” Garberson, the late father of Wheaton alum Julian Garberson ’09, and Denhard’s own father George. While living in West Africa, Shade and Katz travelled extensively. During one trip to Ghana in 1976, Shade became engrossed by the activities of a local wood-carver, working along the Takoradi-Cape Coast Road. He spent several hours helping to carve an Akan stool, which he later purchased from the wood-carver, along with the tools used to carve it. Shade generously donated these tools to Wheaton in 2013. After having been cleaned by student conservators, they can now be used for teaching and research.

Makonde Belly Mask

The college’s most recent acquisition of African art, the belly mask was collected in the Mtawara region of Tanzania in the early 1950s. Created by a Makonde artist, the mask was carved from a single piece of wood to fit on the abdomen of the masquerader who performs it. Such masks are typically danced at initiation ceremonies, or midimu, and funerals. Although worn exclusively by men, belly masks honor both elderly and young women by acknowledging and imitating the struggles of childbirth. Many older masks, such as Wheaton’s, also serve as a historical record of the practice of dinembu, or Makonde body modification. Although no longer widely practiced, these modifications included scarification and tattoos that serve as visible markers of self-discipline and adulthood. This rare object provides Wheaton professors from a variety of disciplines with the opportunity to use the mask in their teaching. Its acquisition was suggested by Associate Professor of Women’s Studies and Art History, Kim Miller who said, “students have historically been particularly interested in researching, writing papers about, and presenting on this type of piece. It will be amazing to be able to use the object itself – firsthand – in my classes.”

Gammon Collection of Ethiopica

Ambassador Giovinella Gonthier ’72 Collection

Sue Williamson

Josh Shade Collection

Makonde Belly Mask

-

Categories:

- Permanent Collection